Tuesday, December 15, 2015

How Did The College Football Playoff Committee Rank Teams?

So just what does the College Football Playoff Committee rank? Countless hours are spent on television, on radio, on the internet, and in newspapers trying to figure that out. At the end of the season, we can try to answer that question.

The first thing you have to realize about the process is that you have to ignore everything Jeff Long says. Jeff Long clearly loves to be playful on television, and so he babbles about "body clocks" and "record vs +.500 opponents" and bad weather and injured players and how "well-rounded" a team is, and other nonsense that is not actually being taken into account.

Before getting to the data, it's worth remembering two things:

1. When people say "Ranking the beat teams" they mean "Ranking the best resumes"

We see this in college basketball all the time. Those of us who understand analytics have to realize that most fans, media, administrators, and other people involved in the sport do not understand analytics. The idea that a team can be better or worse than their resume due to luck in close games does not occur to them. So when they rank the best resumes (or "most accomplished teams") they will announce that they are ranking the best teams. They aren't. To use an example from this college football season: USC is generally rated in good computer ratings as a better team than Iowa. They'd probably be favored in Vegas on a neutral field. Literally zero people are arguing that USC should be ranked ahead of Iowa, and for good reason.

2. The human brain is not actually capable of ranking teams on a dozen different factors

Imagine if you asked a computer code to rank teams by who is best, who played the toughest schedule, who controlled games more, who was most well-balanced, who was the best on the road, and who won a conference championship, all while taking into account injuries, body clocks, lineup changes, and the weather. That computer would give you no answer, because no answer exists. Those are contradictory metrics, often with no objective meaning, and with no weighted value.

Even if Jeff Long created a weighted metric ("We're judging teams 25% on how good they are, 30% on how accomplished they were, 20% on SOS, 10% on team balance, and 15% on game control, with a 5% discount on injuries, and a 5% discount on weather"), nobody would be able to do that kind of math in their head. That's just beyond the human capacity. Human brains will create mental shortcuts.

With that in mind, let's see how closely the playoff rankings compared to a pair of ratings of team quality (S&P and the Sagarin PREDICTOR), a rating of team resume strength (Massey), and the AP Poll, with the y-axis being the root mean square average of all 25 teams ranked by the Playoff Committee each week:

The first thing you notice is that, unsurprisingly, the Playoff Committee rankings aren't even close to the S&P or Sagarin PREDICTOR. They're not rating how good the teams are. We knew that already.

The second thing you notice is that the Playoff Committee rankings are not closing in on any of the computer ratings over time - in fact, they're getting further away. Despite five extra weeks of information between the first and last playoff ranking, the Playoff Committee took no extra information into account. This is consistent with Ken Pomeroy's repeated observations that the preseason AP Poll does a better job of predicting NCAA Tournament success than the postseason AP Poll. The arcane polling rules and procedures actually make the polls less accurate as more games are played and more information is available.

The third thing you notice is that the Playoff Committee ratings aren't really that close to the Massey resume strength rating either. Instead they very closely mirror the AP Poll, and get closer as the season goes along. And in fact, even the final root mean square error for the AP Poll (2.02) is inflated by the teams near the bottom of the Top 25, where less attention is paid. If you look just at the Top 10, the root mean square error is 0.44. Eight of the top ten teams in the playoff rankings are identical to the AP poll, and the other two are a single spot off. In contrast, seven of the top ten teams are at least two spots off their Massey ratings.

In other words:

3. The AP Poll and Playoff Rankings converge over time

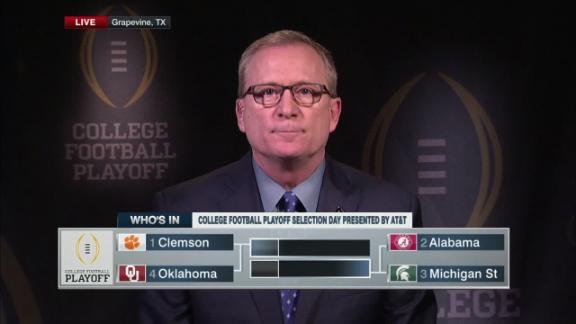

How you want to attribute this "group think" is debatable. Narratives are powerful things in sports, and the narratives feed back on themselves and we all end up agreeing in the end, and that's all that matters. By the end of the season, everybody agreed that Clemson, Alabama, Oklahoma, and Michigan State were the top four teams in some order. The opinions had converged. In contrast, even Massey's resume ratings disagreed there, as that had Ohio State #4.

4. In Other Words, The Playoffs Are A Four Team BCS

As I originally predicted, narratives are too strong in college football for the Playoff Committee to challenge conventional wisdom. We all know the college football ranking rules:

A. Within each conference, teams are ranked by # of losses, so all 11-1 SEC teams will be ahead of all 10-2 SEC teams which will be ahead of all 9-3 SEC teams.

B. When two teams have the same number of losses, the first tiebreaker will be perceived conference strength. So, 1-loss SEC teams will always be ahead of 1-loss Big Ten teams.

C. If two teams are close in the polls (either because they have the same number of losses or, say, a 2-loss team from a superior conference vs a 1-loss team from a weaker conference), then we can start getting into the weeds on who has a better win, or who lost most recently, or whatever other ad hoc argument you want to make.

5. Want to make the Playoffs? Build the easiest schedule possible, get lucky, and win your conference.

Since we're ranking teams by the old fashioned AP Poll rules and not by actual resume strength, the benefit to beating a good team is pretty small. If you have two different Big Ten teams tied with two losses then, sure, having a great non-conference win can be the tiebreaker. But if you're a 3-loss Big Ten team with the world's greatest non-conference SOS you will never be ranked ahead of a 2-loss Big Ten team that played Little Sisters Of The Poor four times. It's just not worth the vastly increased risk of a loss for the slight chance that you'll miss out on the playoffs over a "polling tiebreaker".

Most years, every 1-loss major conference champion will qualify for the playoffs. Certainly any undefeated major conference team will be a lock. So make sure you go undefeated in non-conference play, avoid picking up more than one loss in conference play, and then win your conference title game. That'll get you in.

That's easier said than done, of course. But as Iowa proved this past season, you don't have to be a particularly good team to pull this off. They were borderline Top 25 in most every computer rating, yet came within a single play of winning the Big Ten title game and earning a playoff spot. It took some luck, but it's always going to take luck for any team to make the playoffs. All you can do is improve your odds with smart scheduling, and by playing into the prevailing narratives.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment